Learner Engagement

Learner Engagement asks the questions:

- What provokes student attention?

- What will motivate or excite the students?

- What will sustain student attention and engagement?

Research on Engaging Learners

- Indicates

- “active learning increases examination performance by just under half a SD and that lecturing increases failure rates by 55%” (Freeman, et al., 2013)

- the degree of student engagement is a key predictor of college success (Wankat, 2002; Hake, 1998)

- Students cited motivation (35%), study behaviors (17%) academic preparedness (12%) and interest (11%) as the prime causes of failure in college (Cherif, et al., 2013)

- During lectures “attention alternates between being engaged and nonengaged in ever-shortening cycles throughout the lecture segment,” (Bunce, Flens & Neiles, 2010, p. 1442)

- When “non-lecture pedagogies” are utilized fewer attention lapses were reported (Bunce, Flens & Neiles, 2010, p. 1442)

- The more meaningful the skills, capabilities and/or knowledge to be learned, the faster learning occurs (numerous)

- By “allowing students to use real medical records and to let them prepare for and carry out real therapeutic consultations, improves the rational prescribing skills of medical students during their clinical clerkship,” (Tichelaar, et al., 2014, p. 239)

- Academic optimism significantly contributes to student achievement, (Hoy, Tarter, and Hoy, 2006)

- Significant interactivity in class leads to greater engagement and enhanced student performance, (Blasco-Arcas, et al., 2013)

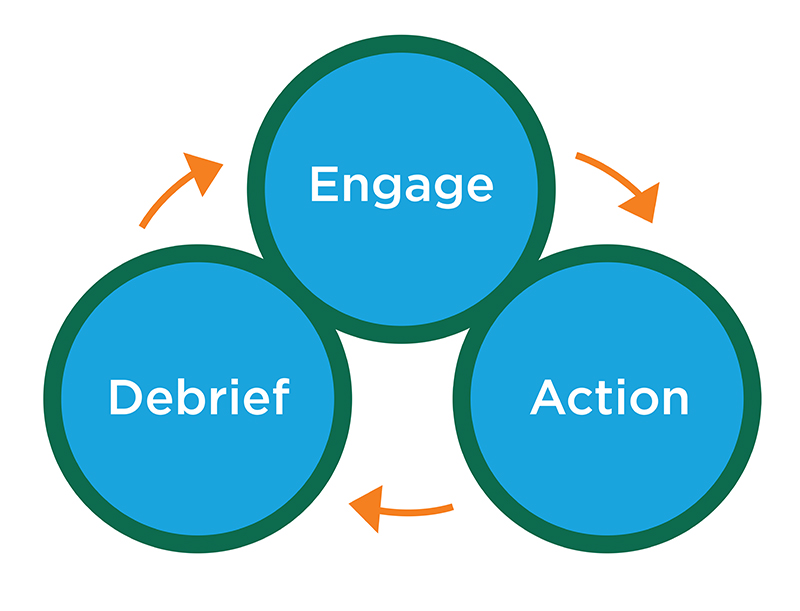

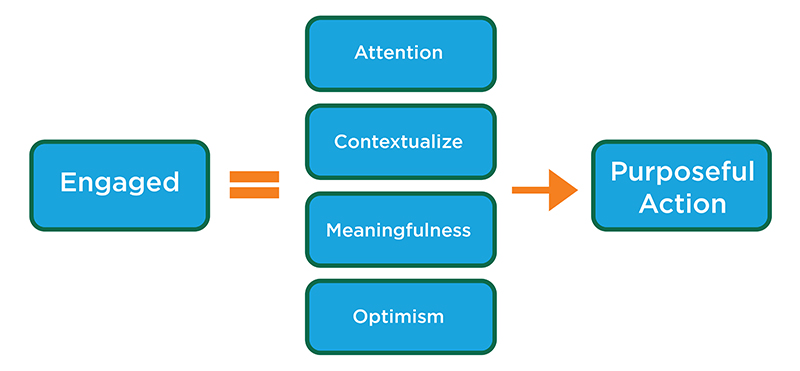

There are at least four key components to effectively engage students in the learning process. These four are interrelated and interdependent. Many of the same strategies address multiple components of learning engagement. The four components are: Attention, Contextualize, Meaningfulness, and Optimism.

Attention

- To gain the attention of learners, consider utilizing:

- Clearly articulated goals/objectives

- Clearly convey the relevance or importance of the learning experience

- Share your enthusiasm for the topic or activity

- Meaningfully involve the students via:

- Physical movement

- Doing something meaningful as an introduction

- Require action, e.g. respond, vote, rank, etc.

- Provide an opportunity to create, share, discuss

- Utilize attractors such as:

- Beauty (specimens, excellent examples, outcomes, etc.)

- Different/peculiar

- Images, sounds, color

- Novelty (new)

- Elicit emotional responses

- Humor

- Controversy

- Outstanding/unique

- Personalize

- Link to something real/meaningful to the learners

- Analogies, models, examples, etc.

Contextualize

All learning occurs in some context or framework. Subsequently, “…habits are a form of slowly accrued automaticity that involves the direct association between a context and a response,” (Wood and Neal, 2007, p. 856). Learners will typically associate what is learned to that specific context. Barker (1978) suggested that the time boundaries and physical setting will be influential in shaping the learned behavior. Bronfenbrenner (1979) proposed that learning occurs as a result of an individual’s interpretation of the context in which learning occurred. Subsequently, the more meaningful and authentic (real) the instructor can make the learning experience, the more likely the learners will appropriately apply the learned knowledge, skills, and capabilities.

Approaches that can enhance the meaningfulness, applicability, and transfer of knowledge, skills, and capabilities being learned include:

- Starting with a common experience, example or framework including

- Mini-case/problem

- Reviewing protocols

- Watching a video, demonstration, role play, etc.

- Analyzing an image, symptoms, etc.

- Utilizing a common learning tool or framework (providing clear context)

- Observation

- Case/Problem

- Video analysis

- Experiments

- Research and data

- Providing developmentally appropriate authentic learning experiences

- Role Plays

- If/then roleplays

- Decision-making trees

- Simulations

- Clinics/practicums

- Role Plays

- Clearly articulating

- Boundaries, framework, or paradigms which will be applied

- Protocols

- Location and/or time

- Linking back to previous learning (familiar)

- Provision of background or case history

Meaningfulness

Meaningfulness is always a key factor in what is learned and how much is learned. A degree of meaningfulness is required so the learner can attend to the new learning. Context is key to meaningfulness. Once context has been established, the new learning also needs to have a varying degrees of meaningfulness to the learners.

- Contextualize (see above)

- Multiple representations of what is to be learned

- Using media, examples, images, data, and other information sources

- Personalize with

- Common experiences (whole class or whole group experiences)

- Link to previous learning/relevance

- Analogies

- Current events (establish a common interpretation)

- Providing developmentally appropriate authentic learning experiences

- Role plays

- If/then scenarios

- Decision-making trees

- Simulations

- Clinics/practicums

- Role plays

- Active learning experiences

- Experimentation/practice

- Evidence-based predictions

- Polls, ratings, rankings, etc.

- Peer sharing, observations, and feedback

- Creating scenarios

- The provision of formative feedback

- During practice sessions, role plays, and other active learning experiences

- Use questions, prompts, what ifs, etc.

Optimism

Engagement relies heavily on learner optimism. The learners need to believe they can learn what is needed to be learned, they can do so in a ‘safe’ learning environment where mistakes, questions, and positive/constructive feedback are established norms. Additionally, the learners need to be optimistic that what they are learning is important, purposeful, and worth their effort. Strategies to enhance and/or maintain optimism among the learners include:

- Establish a course and learning environment where sharing ideas, thoughts and informed

opinions are pertinent to the learning process

- The instructor(s) is also learning from being part of the course/learning experience

- The class as a whole is more knowledgeable than any individual

- Mistakes are part of the process of learning

- How to Learn From Mistakes - TEDtalks

- Create learning experiences that:

- Have multiple possible responses

- Are meaningful and purposeful

- Utilizes scaffolding

- Are challenging

- Provide opportunities for choice in how to:

- Engage with the learning experience

- Express what has been learned (multiple formats)

- Offer opportunities to practice

- Acknowledge that mistakes can be part of the learning process

- Provide opportunities to personalize the learning experience

- Include reflections/debriefs (promote metacognition)

- Include opportunities for:

- Individual, partner and team activities

- Utilize adaptive teaching strategies such as:

- Chunking (segmenting learning into meaningful sections)

- Concept mapping

- Metacognitive opportunities such as deliberate and meaningful reflections of what has/has not been learned

- Provision of positive and constructive formative feedback

- Activities which inherently identifies success/progress (steps)

- Plan for and use teaching approaches and course designs that promote learning!

Monroe’s (1943) Motivation Sequence

- Attention

- Arouse interest; Relevance; Involve audience; Statistics; Question

- Need

- Change; Existing problem; Personalize/localize; Potential consequences

- Satisfaction

- Facts; Background; Examples; Potential solutions/plan;

- Visualization

- Benefits; Personalize/localize; Improvement; Contrast with alternatives

- Action

- What to do to solve the issues; Keep it simple and attainable; Specific to do’s

References

Barker R. & Associates (Eds.). (1978). Habitats, environments, and human behavior: Studies in ecological psychology and eco-behavioral science from the Midwest Psychological Field Station, 1947–1972. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Blasco-Arcas, L., Buil, I., Hernandez-Ortega, B. and Sese, F. (2013). Using clickers in class. The role of interactivity, active collaborative learning and engagement in learning performance. Computers and Education, 62, 102-110

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Bunce, D.M., Flens, E.A., and Neiles, K.Y. (2010). How long can students pay attention in class? A study of student attention decline using clickers. Journal of Chemical Education, 87(12), 1438-1443

Cherif, H., Movahedzadeh, F. Adams, G., and Dunning, J. (2013). Why do students fail? Students’ perspective. A collection of papers on self-study & institutional improvement (29th ed.). The Higher Learning Commission.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S., McDonough, M., Smith, M., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., Wenderoth, M. (June, 2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23)

Hake, R. (1998). Interactive-engagement vs. traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66(1), 64-74

Hoy, W., Tarter, J., and Hoy A. (2006). Academic optimism of schools: A force for student achievement. American Educational Research Association, 43(3), 425-446

Monroe, A.H. (1943). Monroe’s principles of speech (military edition). Chicago, IL: Scott Foresman and Company

Tichelaar, J., van Kan, C., van Unen, R., Schneider, A., van Agtmael, M., de Vries, T., and Richir, M. (2014). The effect of different levels of realism of context learning on the prescribing competencies of medical students during the clinical clerkship in internal medicine: An exploratory study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 71, 237-242

Wankat, P. (2002). The effective efficient professor: Teaching, scholarship, and service. Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA

Wood, W. and Neal, D. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review 114(4), 843-863